Preview: The Conch Paradox

Rethinking Resilience

Read the Preface and opening chapter of The Conch Paradox below. This preview introduces the book's central metaphor and the personal journey that inspired it.

🎧 Listen to the preface

Prefer to listen? Hear the author read the preface in his own voice.

(Note: this recording reflects an earlier version of the preface.)

Book structure

- Chapter 1: The Conch Paradox

- Chapter 2: When the Wave Hits

- Chapter 3: The First Line of Defense

- Chapter 4: The Price of Protection

- Chapter 5: Sensing Change

- Chapter 6: The Rhythm of Endurance

- Chapter 7: The Adaptation Dilemma

- Chapter 8: The Institutional Shell

- Chapter 9: Community Networks

- Chapter 10: The Regeneration Process

- Chapter 11: Beyond Recovery

- Chapter 12: The Resilience Paradox

- Chapter 13: Home

- Acknowledgements

- Notes and References

- Appendix: Recognizing and Working With Your Conch

Preface

This book was born on the Erasmus Bridge in Rotterdam, on a freezing winter night when I finally surrendered.

Forty-eight hours earlier, we'd been under the Aruban sun where our unborn son was diagnosed with a life-threatening diaphragmatic hernia. Now we stood in a Dutch hospital, having fought through bureaucratic barriers and crossed an ocean for experimental surgery that might save him, facing a choice no parent should have to make.

The specialists had presented us with impossible choices: an invasive procedure that could help his lungs develop but carried grave risks of its own, or trust his body's natural capacity and accept deep uncertainty. After an intense hour of deliberation, weighing probabilities and outcomes, we chose to let go. To stop trying to control what we couldn't control.

That's when I ran.

With each stride across the bridge's span, I felt hope and terror pulling me in opposite directions. As I reached the other side, breath clouding in the frigid air, I looked up at my old apartment building. This was where it had all begun for me. A young man from Aruba, fresh start, the world at my feet. I had gained my independence in that building, learned to be an adult in this bold new city. A massive mural now adorned its wall: a mother holding her infant child.

I broke.

Standing there in the cold, staring at that image, all the fear I'd been carrying, all the desperate attempts to analyze and control our way to safety, it poured out of me. I cried in a way I hadn't since childhood.

It's going to be OK.

I had no evidence for this. No data. No analysis. Just surrender, and in that surrender, an unexpected peace that felt more true than any calculation I'd ever made.

Something broke open that night. Not just my fear, but everything I thought I understood about resilience.

This book weaves together three journeys: my family's medical crisis in Rotterdam, my research into how small islands navigate perpetual vulnerability, and a personal transformation I never saw coming. It's about a dangerous misconception that shapes how we respond to every threat we face, from medical emergencies to economic disruption to climate change. We believe that building stronger defenses makes us safer. We assume that specialized protection reduces vulnerability.

We're wrong.

The truth is far more unsettling: the very adaptations that make us most resilient to familiar threats often leave us most vulnerable to novel ones. I discovered this truth praying for my son as he fought for life in a Rotterdam hospital, but the pattern appears everywhere, in Caribbean ecosystems and island economies, in medical systems and marriages, in the protective shells we all build around ourselves.

I've changed some details to protect privacy and illuminate larger truths. The core story, and the paradox it reveals, remains faithful to what we lived.

My hope is that by exploring resilience through both intimate crisis and professional research, you'll recognize your own paradoxes. The places where your greatest strengths have become your deepest vulnerabilities, and the wisdom required to know when to strengthen your defenses and when to risk transformation.

This is the story of how I learned that lesson, and what it might mean for all of us navigating an uncertain world.

Rendell de Kort

Savaneta, Aruba

November 2025

Chapter 1: The Conch Paradox

The Erasmus Bridge stretched before me in the frozen Dutch night. I was dressed absurdly for a January night in Rotterdam — squeezed into winter sports clothes from my student days that made me feel like an overstuffed sausage, borrowed women's gloves from Lay, shorts — whatever we'd thrown into bags during our panicked departure from Aruba. Walking back to our hotel after what I can only describe as a breakdown. Exhausted beyond measure. Emptied of everything.

Just forty-eight hours earlier, we had been under the Aruban sun. Now my wife and I were navigating a foreign medical system, our unborn son's life hanging on decisions no parent should have to make. That evening, we had chosen to forgo experimental surgery and trust his body to heal itself, a surrender that felt like either wisdom or failure, depending on which hour of the night you asked me.

I had told Lay I needed out. I had been strong all day, holding everything together through the consultation, the deliberation, the decision. Now I needed to just be me for a while. She was worried. This was mid-winter Rotterdam, and I was completely unprepared. But I kept telling her: it's fine. When I was a student I ran this city all the time, winter nights, your body warms you up. Eventually she let me go, staying back with Amélie, worried for my safety on top of everything else she was already carrying.

What I couldn't tell her was that part of me wanted the cold. Wanted something physical to fight against, something that would hurt in a way I could understand. The emotional pain was too large, too shapeless. The cold would be simple. The cold would be honest.

And underneath that, the fear I couldn't voice. That we had made the wrong call. That he would die and we would never know if he wouldn't have, had we chosen differently. That we would spend the rest of our lives wondering.

So I ran. And my mind, desperate for anything else to hold onto, wandered to familiar territory: my PhD research. Safer ground. Problems I could think my way through.

Something was crystallizing in the cold, though I couldn't yet name it.

The cockroach and the conch

Months earlier, before any of this began, I'd submitted my first PhD outline on economic resilience in Small Island Developing States. I'd been so proud of it. The queen conch, with its remarkable three-layered shell structure that could withstand tremendous pressure, dissipate force, and contain damage, seemed like the perfect metaphor. Materials scientists studied it. Engineers tried to replicate it. Taking something from the local Caribbean context as a symbol for resilience? I thought it was brilliant.

My supervisors demolished it.

My first supervisor, playing good cop as usual, had been gentle: "Well, maybe you can just mention the conch in the introduction, but let's not talk about that right now. Let's focus on the serious content."

My second supervisor, with the Dutch directness that could feel like a punch to the gut, was more blunt: "OK, using a metaphor is cute. But I don't feel it's working at all. First of all, why are we using a conch as an ideal for resilience? If I'm not mistaken, it's an endangered species, so doesn't sound very resilient to me. If you're looking for a resilient creature, shouldn't we be looking at a cockroach instead?"

A cockroach instead of a conch.

I'd tried to salvage something: "So I just leave that little bit there in the introduction... and maybe the conch lives to fight another day?"

On the webcam, I'd seen him smirk as he agreed that we would proceed like that.

Now, in the frozen Dutch night, those dismissive words began to transform. My supervisor had been right, though not in the way he'd intended.

The queen conch was endangered. Despite its perfect shell. Because of its perfect shell. The very specialization that had protected it for millennia now prevented it from adapting to warming oceans and industrial fishing.

I glimpsed this truth that night but couldn't yet articulate it. It wasn't until more than a year later, after returning to Aruba, that I scheduled another call with my supervisors.

"What if," I asked them, "it's possible to be resilient and vulnerable at the same time? The conch is resilient to shark attacks but vulnerable to global warming. Maybe that's not a weakness in the metaphor. Maybe that's the point."

I held my breath. I'd pushed the conch metaphor before and been gently redirected. Part of me expected another polite dismissal, or worse, the kind of eye-roll you can sense even through a webcam.

Through the screen, I watched my second supervisor's expression shift. Not agreement yet, but something more like contemplation. He was actually considering it.

"Ha," he said. "That's interesting. That does change things. It's not a crazy thought."

Vindication. Relief. More than academic validation: confidence in what I'd discovered through crisis.

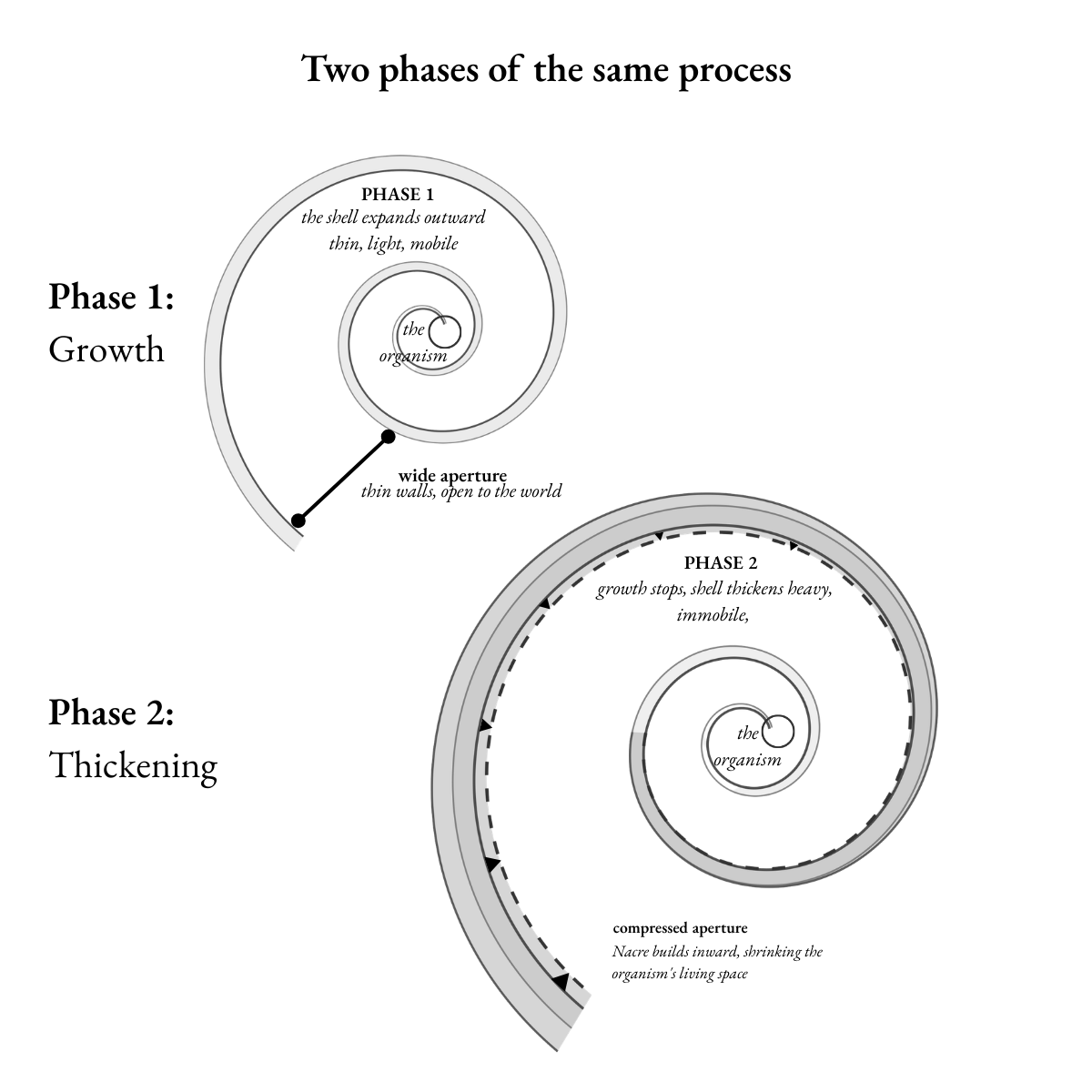

What I would later learn makes the insight even more unsettling. The conch's life unfolds in two phases. As a juvenile, it grows outward along a spiral, adding whorl after whorl. The shell is thin, light enough for waves to roll it across the seafloor. Biologists in Florida call them "rollers." The animal is vulnerable, yes, but it is open to the world: sensing, feeding, moving.

Then, around its fourth year, something shifts. The spiral stops. The conch never adds another whorl. Instead, the shell begins to thicken, depositing layer after layer of nacre on the inside of the wall. The lip flares outward and hardens. The animal becomes heavy, immovable, formidable. And with each passing year, the internal space shrinks. The shell that once grew to house the organism now grows inward, compressing its living chamber, gradually reducing its capacity to reproduce. The protection and the constraint are not even separate materials. They are the same calcium carbonate, laid down in the same process.

The two phases of the queen conch shell. Stylized representation. Phase 1: outward spiral growth (juvenile). Phase 2: inward thickening after growth stops (adult). The shell that grew to protect the organism eventually compresses the space it needs to live. Based on queen conch growth morphology as documented by Stoner et al. and NOAA Fisheries.

The pattern revealed

I started seeing it everywhere. The parallel between my son and the islands I study.

For my son, the resilience measures were medical: feeding tubes that ensured nutrition when he couldn't swallow safely, oxygen monitors that tracked his fragile respiratory system, specialized care protocols that required Rotterdam's expertise. These interventions were saving his life. But they were also creating new dependencies, equipment we couldn't maintain in Aruba, expertise that didn't exist on our island, care routines that would make returning home feel impossible.

It wasn't about any individual decision being wrong. It was about how optimization for known threats systematically creates exposure to novel ones. Protection creating constraint. Strength becoming weakness when the rules change.

Once I saw this pattern in my son's care, I couldn't unsee it in my own work.

The resilience industrial complex

I have a confession to make: I was part of the problem before I understood what the problem was.

When I first began working with the World Bank as a consultant, I learned quickly which words opened doors. A co-writer on one of my early reports suggested adding "resilience" to the title. It sounded right. It was the language that mattered in development circles, the word that made projects fundable, that signaled seriousness, that nobody would question.

So I used it. I added "resilience" to reports without being entirely sure what I meant by it. Early warning systems? Resilience. Emergency relief? Resilience. Long-term capacity building? Also resilience. The word worked. It just didn't mean anything I could defend.

The discomfort grew when I started lecturing to university students. Inevitably, economic resilience would appear on my slides. And I would find myself saying something like: "Resilience is the capacity to bounce back after a shock." The words came out smoothly enough. But I dreaded the follow-up question. What does bouncing back actually mean? Back to what? And what if "back" is the problem?

No student ever pressed me. Maybe they sensed my uncertainty. Maybe they were writing down the definition for the exam and moving on. I knew I was mumbling through something I didn't understand, using language that sounded sophisticated while hoping nobody would notice it was hollow.

This unease is what eventually drove me to study resilience seriously. I needed to understand what I'd been selling.

What I discovered was a self-perpetuating system I came to think of as the "resilience industrial complex." It's become like bacon. You can add it to almost anything for extra flavor. Resilient cities. Resilient supply chains. Resilient leadership.

In practice, it usually means: bounce back to normal as quickly as possible. Build higher seawalls. Develop faster recovery protocols. Add more redundancy to critical systems. These aren't wrong, exactly. But they assume the future will look like the past: just bigger waves, same ocean. What if it's a different ocean entirely?

The resilience industrial complex is comfortable because it doesn't require questioning your core approach.

Nassim Taleb exposed part of this problem. His Black Swan revealed how spectacularly we fail at predicting the rare events that reshape everything, the outliers our models systematically miss. The conch paradox addresses something different. The problem isn't only that we can't predict black swans. It's that our successful adaptations to yesterday's challenges become tomorrow's constraints. The conch didn't fail to predict warming oceans. It simply couldn't stop being a conch.

The dead-end problem

But there's a worse problem. The resilience discourse has a fatal blind spot: it focuses entirely on how well you can absorb shocks while traveling your current path. It never asks whether the path itself leads somewhere worth going.

There's a name for this trap: path-dependency. Once you see it, you can't unsee it. Past choices constrain future options until alternatives become nearly impossible to pursue. Each investment in your current approach makes it harder to change direction. Each success reinforces the trajectory. The better you get at what you do, the more difficult it becomes to do anything else.

The warnings had been circulating for years. At conferences, in policy discussions, in complaints at family gatherings. Everyone agreed in principle. And year after year, another hotel permit approved, another construction crane on the horizon. People blamed corrupt politicians trading favors for permits. But I came to see it differently. The problem wasn't individual corruption. It was structural. Every hotel that opened created jobs that created voters that created pressure for more growth. Each success funded the next investment. Each investment deepened the dependency.

You feel it now in ways that don't show up in economic reports. You feel it stuck in traffic that doesn't move because a cruise ship has unloaded thousands of passengers walking everywhere at once. You feel it at beaches that used to be on postcards, now loud with music and jet skis and bodies competing for sand. You feel it underwater most of all. I learned to snorkel in waters full of parrotfish and brain coral. Now I see bleached white skeletons and anchors, boats full of tourists floating where reef used to be. A few small fish if I'm lucky. Anyone who has watched a favorite place consumed by its own success knows this feeling.

It hadn't even started as a choice.

When the oil refinery that had anchored Aruba's economy closed in 1985, there was no grand deliberation, no stakeholder consultations weighing alternative futures. There was fiscal panic. The government needed revenue. The island needed foreign exchange. Tourism wasn't chosen through careful resilience analysis. It was the only option that could generate money fast enough to keep the lights on.

But there's a difference between choosing tourism and going all in. The initial pivot was survival. What followed was appetite. The government expanded hotel capacity well beyond what advisors recommended, and the rewards came so fast that restraint looked foolish. Except the overshoot created problems the island had never faced. Each expansion funded the justification for the next. Forty years later, Aruba is still making the same bet at larger stakes.

When COVID-19 grounded international flights, we discovered we had spent decades becoming resilient to everything except the one thing that actually happened. We could weather hurricanes, financial crises, regional instability. We had proven this repeatedly. What we couldn't survive was the disappearance of tourists themselves. Our resilience had been path-dependent: extraordinarily robust along one trajectory, catastrophically fragile if that trajectory was blocked.

The question conventional frameworks never ask is: resilient toward what end? You can be perfectly resilient heading toward a cliff.

The conch has been perfecting its shell for millions of years. By any conventional measure of resilience, it succeeded brilliantly, right up until the moment the definition of success changed entirely. The threat wasn't bigger predators requiring thicker armor. The threat was a transformation of the environment that made the entire armor strategy irrelevant.

The deeper dimension

There's a dimension I didn't fully grasp until much later, though I had been battling it from the first night on that bridge. It concerns the shell we build and what we do when we feel threatened.

When a predator approaches, the conch's instinct is retreat and fortification, withdrawing deep into its spiral chamber and sealing the entrance with its operculum, that hard, claw-like plate that fits the opening perfectly. Against a shark or an octopus, this works brilliantly. The predator can't reach the vulnerable organism tucked inside. The conch waits, sealed and safe, until danger passes.

Anyone who has seen a conch harvested knows what happens next. The fisherman wading through shallow water doesn't need to defeat the conch's defenses. He simply picks up the sealed shell and carries it to shore. Later, at his convenience, he'll punch a hole through the spiral, right where the muscle attaches, and extract the animal completely. The conch's perfect sealing behavior, so effective against natural predators, becomes its doom against a threat it never evolved to recognize. By sealing itself in, it guaranteed its own capture. It couldn't flee because it was too busy fortifying.

This is the deeper lesson: we don't just have shells; we retreat into them when threatened. And sometimes that instinct, so effective against familiar dangers, leaves us trapped and helpless when the nature of the threat changes.

The conch paradox has three dimensions. The first is structural: every protective adaptation creates new vulnerabilities. The second is directional: you can be perfectly resilient while heading toward disaster. The third is behavioral: when we feel threatened, we instinctively retreat into whatever shell we've built, even when that retreat guarantees our capture rather than our safety.

What I would discover over the months and years that followed is that these three dimensions don't just apply at one scale. The same paradox operates in the body, the family, the organization, and the economy. Kayden's medical protections creating new dependencies. Our family's coping mechanisms becoming barriers to intimacy. The World Bank's institutional expertise becoming rigidity. Aruba's tourism success becoming a trap. The scale changes. The mechanism doesn't.

Can the very adaptations that ensure survival in one era guarantee extinction in another?

This question would haunt the months ahead as we navigated systems designed to protect but built to constrain.

Every protective adaptation simultaneously creates new vulnerability. Optimization for known threats systematically generates exposure to novel ones. There is no universal path to resilience because every protective measure reshapes the threat landscape it was designed to address.

Structural: Protection creates constraint. The conch's shell defeats predators but prevents escape from fishermen. Medical interventions that saved my son created dependencies we couldn't sustain at home.

Directional: Resilience without direction is dangerous. Aruba became extraordinarily robust along one economic trajectory and catastrophically fragile when that trajectory was blocked. Path dependency means you can be perfectly resilient heading toward a cliff.

Behavioral: Retreat instinct under threat. The conch seals itself inside its shell when danger approaches, which works against sharks and guarantees capture by fishermen. We do the same: withdrawing into familiar defenses precisely when we need to adapt.

Lipsey and Lancaster's general theory of second best (1956) proves that in a world with multiple imperfections, fixing one doesn't necessarily improve outcomes. Rodrik extends this to development policy. The conch paradox extends it further: building protection against one threat can create vulnerability to others. This is why the resilience industrial complex, with its additive logic of stacking interventions, fundamentally misunderstands how complex systems behave.

Want to read the complete story?

Subscribe to receive launch updates, exclusive preview chapters, and behind-the-scenes insights from the research journey.

Subscribe for updates